The forgotten of the forgotten

Researched and written by Daniel Townsend

Chinese Labour Corps

In the run up to the centenary of the end of the First World War there has been an ever increasing effort to recognise all of those whom played a part in the war effort. In terms of non-British forces during WWI, ANZAC and American troops receive the limelight. Forces from elsewhere in the empire, including those from China, have failed to gain the same recognition indeed, the Chinese Labour Corps (CLC) have been described as “the forgotten of the forgotten”(1).

While Britain employed an estimated 140,000 Chinese labourers during the war(2), their only memorials outside of France (where they are relatively few in number) are the small number of war graves bearing their names. These are notably located in towns with ports: Liverpool, where troop ships would arrive following their transatlantic voyage from Nova Scotia, Canada; and Folkestone, often the last stop prior to being shipped to France and the western front.

Though there has been a campaign to create a memorial to the Chinese Labour Corps in London, China Daily reports that it took until 2017 for this campaign to be realized(3). The memorial, in the form of a 9.6 metre high marble column is located in East London near the Royal Albert Docks.

Initially, the British Government did not seek Chinese labour. The Chinese government was keen to maintain their neutrality rather than being sucked in to a European war and hence could not offer a fighting force(4). This, combined with the general hostility from the British War Office regarding the idea of fielding native troops in a war against a European army, meant China’s potential remained untapped.

It was not until the tumultuous defeats suffered by British forces across the Western Front in 1916 and resulting loss of hope that Kitchener’s new volunteer army would bring a swift ending to the war, that the need for a new labour force became evident. As both skilled and unskilled British labourers were destined for the front lines as a result of conscription, more and more vital support roles were left unfilled. To remedy this, it became necessary to create new labour forces for which the British Government “had to look to her empire and beyond”(5).

After much debate within the War Cabinet it became apparent that the war could not continue to be conducted without help from Imperial troops. Winston Churchill argued in parliament:

“I would not even shrink from the word ‘Chinese’ for the purpose of carrying out the war. These are not times when people ought in the least to be afraid of prejudices.”(6)

Following the decision by the War Cabinet to utilize Chinese labour, a plan was drawn up for recruitment centres within the British Crown Colony of Hong Kong. This was soon scrapped: a memo from the colonial office claimed that choosing to recruit in Hong Kong meant, “the men would be Cantonese and Cantonese are not accustomed to a cold climate. This might be sufficient to prevent the scheme being carried out.”(7)

As a result it was decided that volunteers would be drawn from China’s northern provinces which offered convenient sea ports for the transportation of recruits, an impoverished local community attracted to the relatively high wages offered by the British and a difficult climate of “summer sandstorms and dust”(8). This, it was thought, would supply a force of men more adaptable to European climes. Initially, the port town of Weihaiwei became the centre of British recruitment, later moved to Qingdao following its liberation from German hands, owing to its better infrastructure.

Though there was certainly no shortage of potential recruits for the CLC, the rigorous nature of the selection tests meant that many were left out. Indeed, it is estimated that up to 60% of the volunteers were rejected due to failing their initial medical examinations(9). Of those declared medically unfit, a large number had problems with their eyes owing to the aforementioned weather conditions in their home provinces. Medical issues such as “trachoma, tuberculosis, venereal disease and bad teeth”(10) were also prevalent as reasons for rejection.

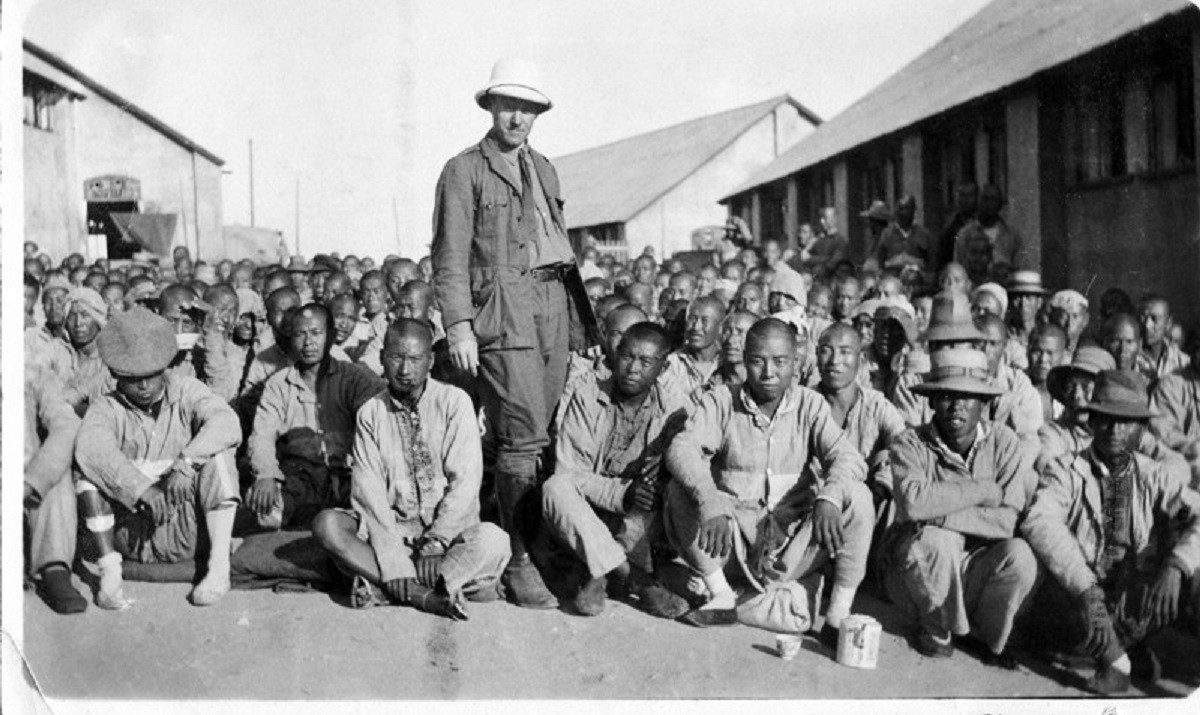

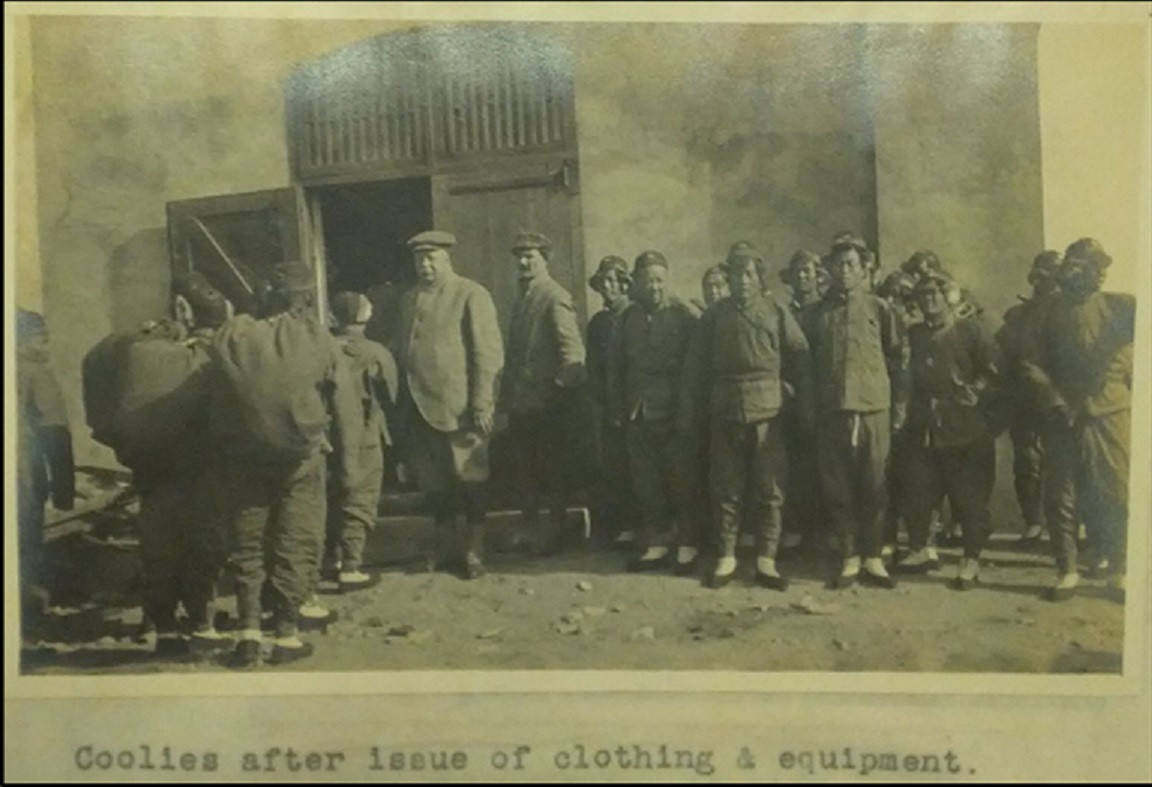

Following this ordeal, accepted troops were issued with uniforms bearing the CLC regimental crest and the motto “Labour Vincit Omnia”(11) (Labour conquers all) and placed in to regiments under the command of British officers.

Before they embarked en route to Britain and the Western Front the labourers were issued with serial numbers and dog tags. Initially these numbers were sprayed on the wrist of each recruit. Later, when it was decided that this was dehumanizing, they were instead issued with brass dog tags to wear around their wrists(12).

These numbers were more significant than the numbers of their Western counterparts, replacing their names and allowing them to be identified more easily by British officers - in spite of the presence of translators who were able to communicate the officers' orders to the labourers. The importance of these numbers within the CLC is evidenced by their appearance on CLC war graves across France(13).

Diverting allied shipping to transport thousands of men from China to Europe was already a difficult task from a logistical perspective. The sheer distance and the number of stops required en route meant that no voyage would prove easy.

The Suez and Panama canals along with the longer route via Cape Town all provided their own dangers. The often rough nature of the seas were a problem, since few of the labourers had ever travelled on water before(14), sickness and illness were commonplace. Further and more deadly was the threat of German U-boats patrolling allied shipping routes. Indeed, the fears of The Admiralty were realized when, in 1916, a ship carrying workers to France was sunk in the Mediterranean, with the loss of 543 lives(15).

The tragedy of this loss led the British to identify new routes for transporting troops to France, one less susceptible to the perils of U-boat warfare in the Mediterranean. Though the intentions may have been good, the implementation of a plan, which involved subjecting 84,000 men to a grueling three-month voyage, resulted in the loss of “hundreds, if not thousands”(16) of lives.

The journey consisted of sailing across the Pacific Ocean from China to Vancouver, a six-day train ride across Canada to Halifax, Nova Scotia, here embarking for a voyage across the North Atlantic to Liverpool, where the troops would be organised before being finally moved to the Western Front to perform their duties.

Though no journey could be without its perils in wartime, the most dangerous and damning element of the transportation of the CLC to Britain was “kept secret for years in the then British dominion”(17).

Following the entry of Chinese troops in to dock at Vancouver, British Columbia they were immediately “herded, like so much cattle”(18) in to goods trains which would be sealed for the journey until their arrival in Halifax, Nova Scotia approximately six days later. This inhuman treatment, embodied by the Canadian authorities who “treated the Chinese like prisoners rather than allies”(19), was agreed upon by the governments of the two respective countries to avoid incurring landing taxes on each member of the CLC.

Following this fraught journey, the men of the CLC eventually arrived in France as well as English ports such as Newhaven and Folkestone, where they worked for the remainder of the war.

The importance of the port of Newhaven to the war was pivotal, being an ideal place to dispatch army supplies to France and to disembark wounded men from hospital ships for their onward journey to convalescence centres on the south coast.

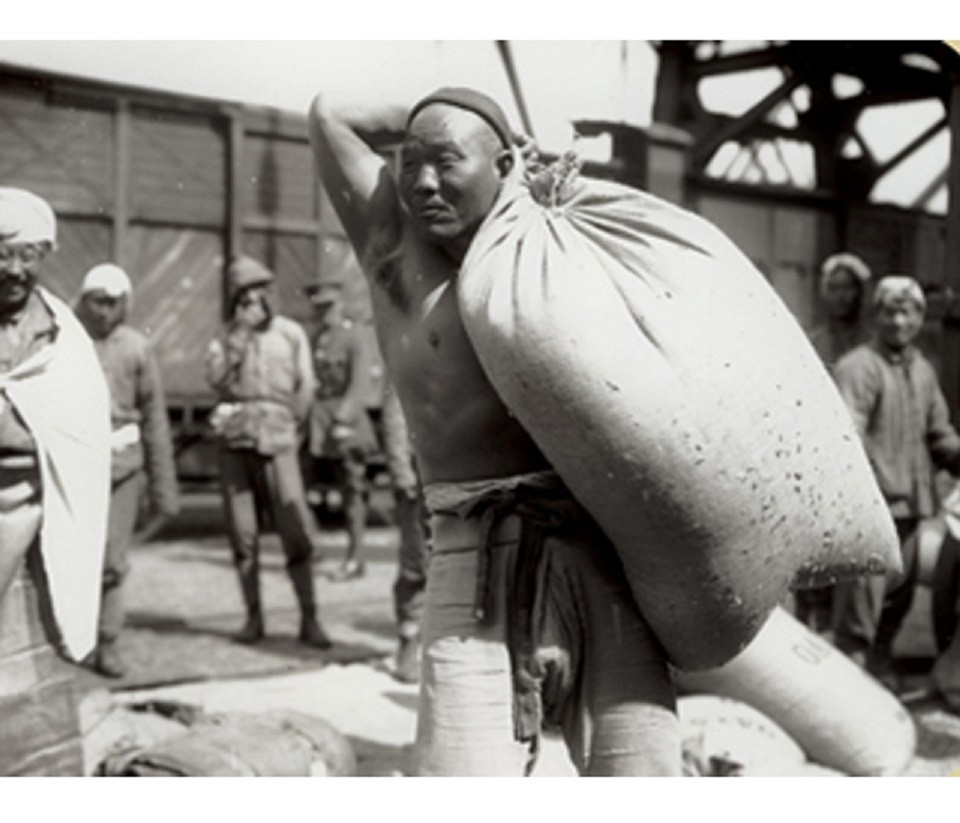

After 1917, Chinese labourers were employed in various duties at the docks, primarily unloading and loading supplies on to ships. Hence, the sight of Chinese labourers would have been a common one within Newhaven during the war(20).

If, however, their treatment in Sussex was anything like their treatment on the Western Front, contact between the Chinese contingent and the locals would have been minimal. Typically, the CLC were kept in separate camps and barracks than other colonial soldiers and white soldiers, being strictly disciplined by the British who maintained a “racist haughtiness”(21) for the duration of the war.

The contracts given to the Chinese regiments forbade them from participating in any fighting. Instead, they were given support tasks: moving shells, dealing with unexploded bombs, unloading transports and digging trenches, even agriculture and forest management(22). The multifarious nature of their work meant communication was key, but as one American soldier found out when shouting “let’s go” to a number of Chinese workers, (who believed he had shouted “Gou” meaning dog in Chinese) and nearly inciting a rebellion(23), language barriers were clearly one issue the army had yet to overcome.

Their lack of front line duty did not make the CLC's work safe, even work carried out far behind the lines had its associated dangers. Dealing with unstable shells and explosives led to a range of accidents resulting in dismemberment and loss of life while seaports, depots and ammunition stores were often targets for air raids and long-range bombardments(24).

When the armistice was signed in 1918 there were still 96,000 men serving with the CLC(25) and, though the British contingents were all repatriated by September 1920(26), many of the French recruits remained, to be issued with various post-war tasks. Of these, battlefield clearance was in many ways more dangerous than the wartime work issued to the CLC. This “dangerous and unpleasant”(27) task often involved dealing with infection from the mass of bodies left on the battlefield and unexploded shells and bombs, which were unstable and dangerous to move.

Beyond this brief snapshot in to the work of the CLC there is relatively little information. It is a striking testament to the description of the CLC as the “forgotten of the forgotten”(28) that so little study nor interest has been paid to the Chinese Labourers so vital to the war effort until the years leading to its centenary.

Though a memorial is being constructed in London to remember the importance of the role played by these men, it is notable that this is the first of its kind. Prior to this there has been little fanfare afforded to the notion of Chinese sacrifice, in spite of the fact that some modern estimates place the CLC death toll at 20,000(29).

References

(1) Kennedy, Maev. ‘First World War’s Forgotten Chinese Labour Corps to get recognition at last’. The Guardian 14/8/14 accessed 14/8/18

(2) Calvo, Alex and Qiaoni, Bao. ‘Forgotten voices from the Great War: The Chinese Labour Corps’. The Asia-Pacific Journal 13:51 (2015): pp. 1-13. They note that 140,000 is a ‘conservative’ estimate

(3) Leung, Bo. “East London Memorial to honor China’s World War I contribution” Chinadaily.com 12/8/17 accessed 20/8/18

(4) China in fact did offer a fighting force of 50,000 but only in exchange for the British retaking Qingdao, an offer Britain rejected, fearing the idea of giving China leverage. Boehler, Patrick. ‘The Forgotten Army of the First World War’. South China Morning Post accessed 17/8/18

(5) ‘The Chinese Labour Corps at the Western Front’. Commonwealth War Graves Commission 3/1/12 accessed on 17/8/18

(6) Boehler, Patrick. South China Morning Post accessed 17/8/18

(7) Kumlersakul, Pad. ‘Chinese Labour Corps on the Western Front’. Blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk 18/1/17 accessed 17/8/18

(8) Fawcett, Brian C. ‘The Chinese Labour Corps in France 1917-1921’. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Hong Kong branch Vol. 40 (2000): P.33-111. P.36

(9) Ibid P.36

(10) Ibid P.36

(11) Ibid P.37

(12) Calvo and Qiaoni. The Asia-Pacific Journal, 2015. P.4

(13) Kempshall, Chris. ‘Chinese Labourers in Newhaven’ eastsussexww1.org.uk. Accessed 17/8/18

(14) Kumlersakul, Pad. ‘Chinese Labour Corps on the Western Front’. Blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk 18/1/17 accessed 17/8/18

(15) Calvo and Qiaoni. The Asia-Pacific Journal, 2015. P.4

(16) Boehler, Patrick. ‘The Forgotten Army of the First World War. South China Morning Post accessed 17/8/18

(17) Ibid.

(18) Ibid.

(19) Feltman, Brian K. ‘Review: Xu Guoqi ‘Strangers on the Western Front in the Great War’ Harvard University Press, 2011.’ European History Quarterly 42:4(2011): pp.731-732. P.731.

(20) Kempshall, Chris. ‘Chinese Labourers in Newhaven’ eastsussexww1.org.uk accessed 17/8/18

(21) Feltman. ‘Review’ P.732.

(22) Calvo and Qiaoni. The Asia-Pacific Journal, 2015. P.1

(23) Calvo and Qiaoni. The Asia-Pacific Journal, 2015. P.5

(24) ‘The Chinese Labour Corps at the Western Front’ Commonwealth War Graves Commission 3/1/12 accessed 17/8/18

(25) ‘Service at the Noyelles-sur-Mer Chinese Cemetery’ somme-battlefields.com accessed 20/8/18

(26) Kumlersakul, Pad. 18/1/17 accessed 17/8/18

(27) The Chinese Labour Corps at the Western Front’ Commonwealth War Graves Commission 3/1/12 accessed 17/8/18

(28) Kennedy, Maev. ‘First World War’s Forgotten Chinese Labour corps to get recognition at last’ The Guardian 14/8/14 accessed 14/8/18

(29) Ibid.